Introduction

For decades, diabetes screening has revolved around a single, seemingly decisive number that is blood glucose. If fasting glucose falls within a laboratory-defined “normal” range, most individuals are reassured that their metabolic health is intact. This reassurance is often reinforced by annual health checkups, insurance screenings, and even public health messaging that equates diabetes risk almost entirely with sugar levels. Yet clinical reality tells a more uncomfortable story. A large proportion of people who eventually develop type 2 diabetes spend years, sometimes decades, being told that their glucose is normal.

This gap between reassurance and reality exists because glucose is not an early warning signal. It is a late-stage outcome. The metabolic system is remarkably adaptive and does not fail abruptly. Long before glucose begins to rise, the body compensates silently by producing more insulin to maintain glucose balance. This compensatory phase, marked by rising fasting insulin and progressive insulin resistance is where type 2 diabetes truly begins, even though it remains invisible on routine blood reports.

At iThrive, we do not view diabetes as a disease of sugar excess. We see it as a progressive failure of metabolic regulation. When viewed through this lens, insulin dynamics offer far greater insight into risk and trajectory than glucose values alone. Understanding the difference between fasting insulin and fasting glucose is therefore not a technical nuance, it is foundational to predicting, preventing, and reversing metabolic disease.

What Fasting Glucose Actually Measures and What It Misses

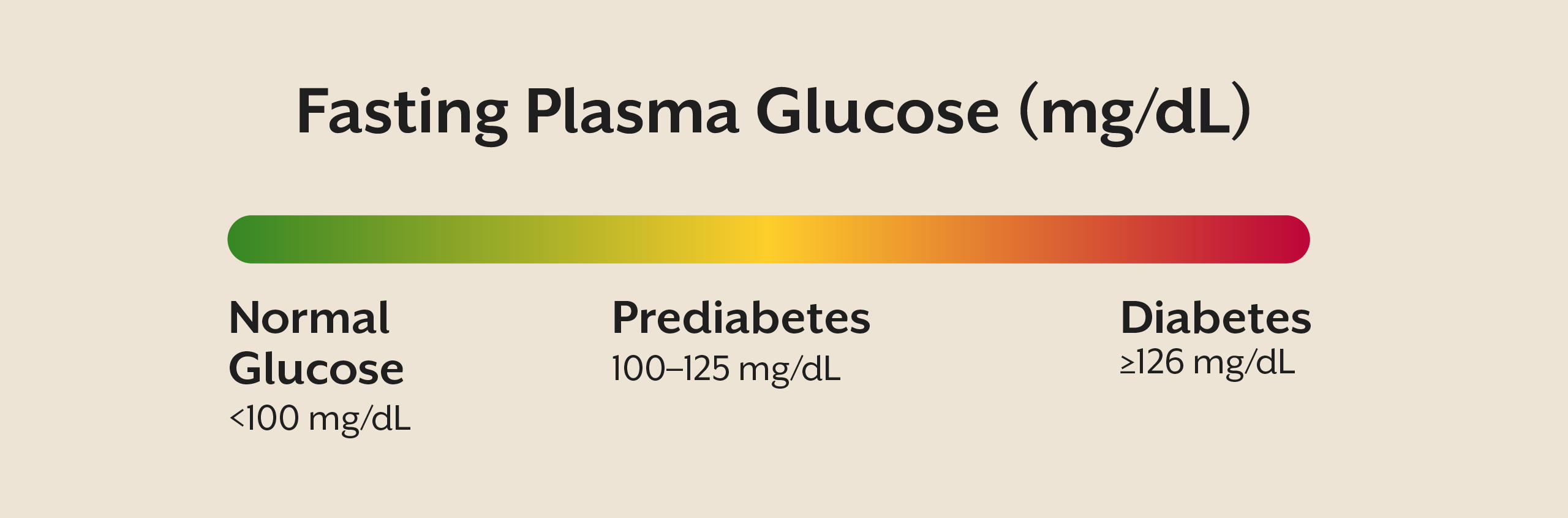

Fasting glucose measures the concentration of glucose circulating in the blood after an overnight fast. Clinically, it is used to identify overt disturbances in glucose regulation, commonly classified into normal, prediabetes, and diabetes ranges. On paper, this seems logical: if glucose is high, regulation must be impaired. However, this interpretation overlooks a critical question as to how much metabolic effort was required to keep glucose within range?

Fasting glucose reflects the end result of multiple physiological processes working together, including insulin secretion, hepatic glucose production, muscle uptake of glucose, and hormonal counter-regulation. What it does not capture is the strain placed on these systems to maintain balance. A normal glucose value can therefore exist in two very different metabolic realities: one where regulation is effortless, and another where regulation is maintained only through excessive insulin output.

The limitation is not the test itself, rather it’s what the test represents. Fasting glucose reflects the end result of multiple metabolic processes, not the strain those processes are under.

Why glucose stays normal for so long

In the early stages of insulin resistance, cells particularly in muscle and liver become quite less responsive to insulin’s signal. To compensate, the pancreas increases insulin secretion. As long as pancreatic beta cells are capable of sustaining this higher output, glucose levels remain within normal limits. This compensatory mechanism is highly effective and can persist for years.

The problem is that this apparent stability masks progressive metabolic dysfunction. Elevated insulin promotes fat storage, suppresses fat oxidation, and alters appetite regulation. Over time, this creates a metabolic environment that favours weight gain, inflammation, and further insulin resistance. By the time fasting glucose finally begins to rise, the system has already endured prolonged stress, and the most reversible window has often passed.

Fasting Insulin - The Hidden Signal of Metabolic Stress

Fasting insulin measures how much insulin the pancreas must produce to maintain glucose balance during a fasting state. Unlike glucose, insulin levels rise early in the course of metabolic dysfunction, long before any diagnostic thresholds are crossed. This makes fasting insulin a marker of metabolic effort rather than metabolic failure.

In a metabolically healthy individual, fasting insulin remains low because cells respond efficiently to insulin’s signal. After meals, insulin rises transiently and then returns to baseline as glucose is cleared. In insulin resistance, this baseline shifts upward. Insulin no longer returns to truly low levels, indicating that the system is under constant demand even in the absence of food intake.

Elevated fasting insulin tells a deeper story. It signals that cells are becoming resistant, that the pancreas is under chronic compensatory stress, and that metabolic flexibility, that is the ability to switch between fuel sources, is declining. Importantly, this state can exist for years without any abnormal glucose readings, making it invisible to standard screening.

At iThrive, fasting insulin is never interpreted in isolation. It is contextualised alongside clinical history, body composition, lipid patterns, inflammatory markers, and lifestyle factors. The goal is not merely to label insulin resistance, but to understand why insulin demand is rising in the first place.

Fasting Insulin vs Fasting Glucose

Type 2 diabetes is often approached as a threshold-based diagnosis: glucose crosses a line, and disease is declared. In reality, diabetes unfolds along a continuum. Viewing insulin and glucose along a timeline reveals why their predictive value differs so dramatically.

In the earliest phase, insulin resistance begins to develop at the cellular level. Fasting insulin rises as the pancreas compensates, while fasting glucose remains normal. As dysfunction progresses, insulin levels climb higher and glucose may enter a borderline range. Eventually, pancreatic beta cells can no longer sustain compensation. Insulin output becomes inadequate relative to resistance, and glucose rises into the diabetic range.

This sequence explains why glucose is a late marker and insulin an early one. Relying on fasting glucose alone means intervening only after years of hidden metabolic stress have already occurred.

Insulin Resistance - The Common Denominator

Both elevated fasting insulin and eventual glucose dysregulation arise from a shared underlying process: insulin resistance. Importantly, insulin resistance is not limited to blood sugar control. It is a systemic condition that affects multiple metabolic pathways simultaneously.

As insulin signalling weakens, lipid metabolism becomes dysregulated, promoting excess fat storage and impaired fat release. Inflammatory pathways are activated, mitochondrial efficiency declines, and appetite and satiety signalling become distorted. These changes explain why insulin resistance is often accompanied by weight gain, fatty liver, dyslipidaemia, PCOS, and chronic fatigue long before diabetes is diagnosed.

Why Most Diabetes Screening Still Misses the Early Window

Despite growing evidence, fasting insulin is not routinely included in standard screening. This omission is not due to lack of relevance, but rather historical reliance on glucose-centric guidelines and a healthcare model oriented toward diagnosis rather than prevention.

For individuals with a family history of diabetes, persistent weight challenges, PCOS, or subtle metabolic symptoms, ignoring fasting insulin means missing the most actionable phase of disease development. By the time glucose rises, opportunities for early reversal are significantly reduced.

At iThrive, this missed window is precisely where root-cause assessment begins. Instead of asking whether sugar is high, we ask what the metabolism is signalling right now and why.

Interpreting Risk - Markers Mean Nothing Without Context

An elevated fasting insulin does not mean diabetes is inevitable. It means the system is under strain. The source of that strain determines both risk and reversibility.

Chronic overnutrition, sedentary muscle tissue, sleep disruption, stress-related cortisol elevation, inflammatory dietary patterns, and micronutrient deficiencies can all drive insulin resistance. Without identifying these drivers, focusing on numbers alone becomes misleading.

This is why Alive programmes prioritise mapping cause, compensation, and consequence. As discussed in our earlier piece on metabolic health restoration, numbers gain meaning only when interpreted within a broader physiological context.

Can Lowering Insulin Reduce Diabetes Risk?

Lowering fasting insulin can reduce diabetes risk, but only if the approach addresses the underlying drivers of insulin resistance. Superficial strategies that temporarily suppress glucose without improving insulin sensitivity may delay diagnosis but do not change disease trajectory.

Sustainable improvement requires enhancing muscle insulin sensitivity, reducing inappropriate hepatic glucose output, restoring metabolic flexibility, and correcting circadian and stress-related disruptions. This is where structured root-cause analysis becomes essential. For individuals uncertain about the origin of their insulin resistance, a clinical review can help clarify whether nutrition, stress physiology, inflammation, or hormonal patterns are the primary drivers.

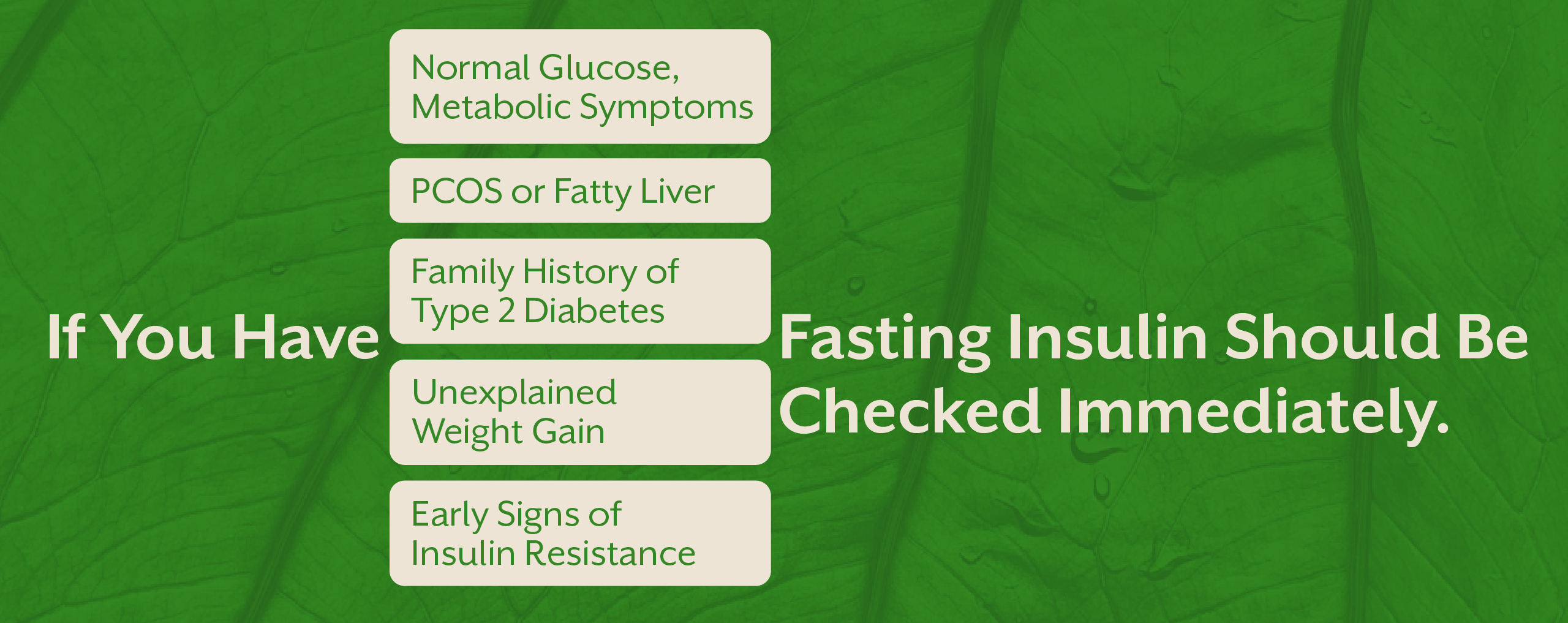

Who Should Prioritise Fasting Insulin Testing?

Fasting insulin testing is particularly valuable for individuals whose glucose appears normal but whose metabolic health tells a different story. This includes those with a family history of type 2 diabetes, PCOS, fatty liver, unexplained weight gain, or early signs of insulin resistance.

For these individuals, waiting for glucose to rise is not prevention, rather it is postponement. Identifying metabolic strain early creates an opportunity to intervene before irreversible damage occurs.

Key Takeaway

Fasting glucose tells us when metabolic compensation has failed, but fasting insulin reveals when that compensation has begun. If the goal is to predict, prevent, and meaningfully reverse type 2 diabetes, insulin and not glucose offers the earlier and more actionable signal. True metabolic care requires moving beyond sugar thresholds toward understanding why insulin demand is rising in the first place. At iThrive, this shift from numbers to mechanisms allows intervention during the most reversible phase of metabolic dysfunction, long before irreversible damage sets in.

Subscribe to our newsletter and receive a selection of cool articles every week

.png)

.webp)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.webp)