Introduction

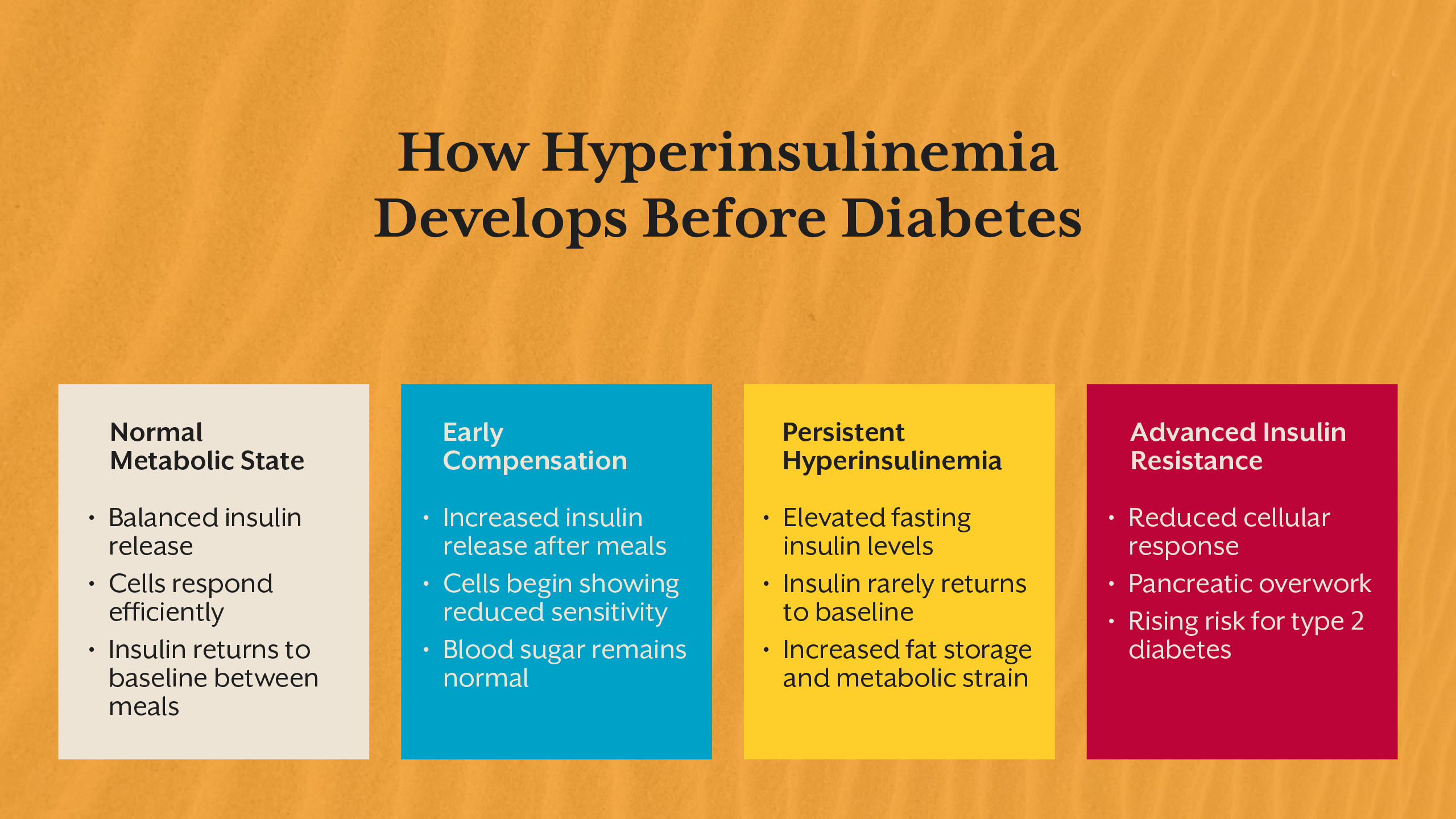

Modern metabolic disease rarely begins with high blood sugar. Long before glucose levels cross diagnostic thresholds, the body is already compensating, adapting, and quietly struggling to maintain balance. At the center of this compensation lies insulin.

Hyperinsulinemia refers to a state of chronically elevated insulin levels in the bloodstream. It is one of the earliest detectable signs of metabolic dysfunction, yet it remains largely invisible in routine healthcare. Most individuals with hyperinsulinemia are told their blood sugar is “normal” and reassured that nothing is wrong, even as their metabolism is under increasing strain.

This silent elevation of insulin is not benign. It drives insulin resistance, alters fat storage, disrupts hormonal signaling, and lays the foundation for conditions such as type 2 diabetes, fatty liver disease, PCOS, and cardiovascular disease. Understanding hyperinsulinemia requires shifting attention away from glucose alone and toward the hormonal systems regulating energy.

This blog will explore what hyperinsulinemia is, how it develops, why it goes undetected, how it manifests in the body, and why identifying it early changes the entire trajectory of metabolic health.

What Is Hyperinsulinemia, Really?

Hyperinsulinemia is defined by persistently high insulin levels relative to physiological need. Insulin is secreted by the pancreas in response to rising blood glucose, but its role extends far beyond glucose control. It signals cells to store energy, suppress fat breakdown, and shift metabolism toward growth and storage.

In a healthy system, insulin rises briefly after meals and returns to baseline during fasting. In hyperinsulinemia, insulin remains elevated for prolonged periods, including during fasting. This elevation reflects a loss of metabolic efficiency, where the body must produce more insulin to achieve the same effect.

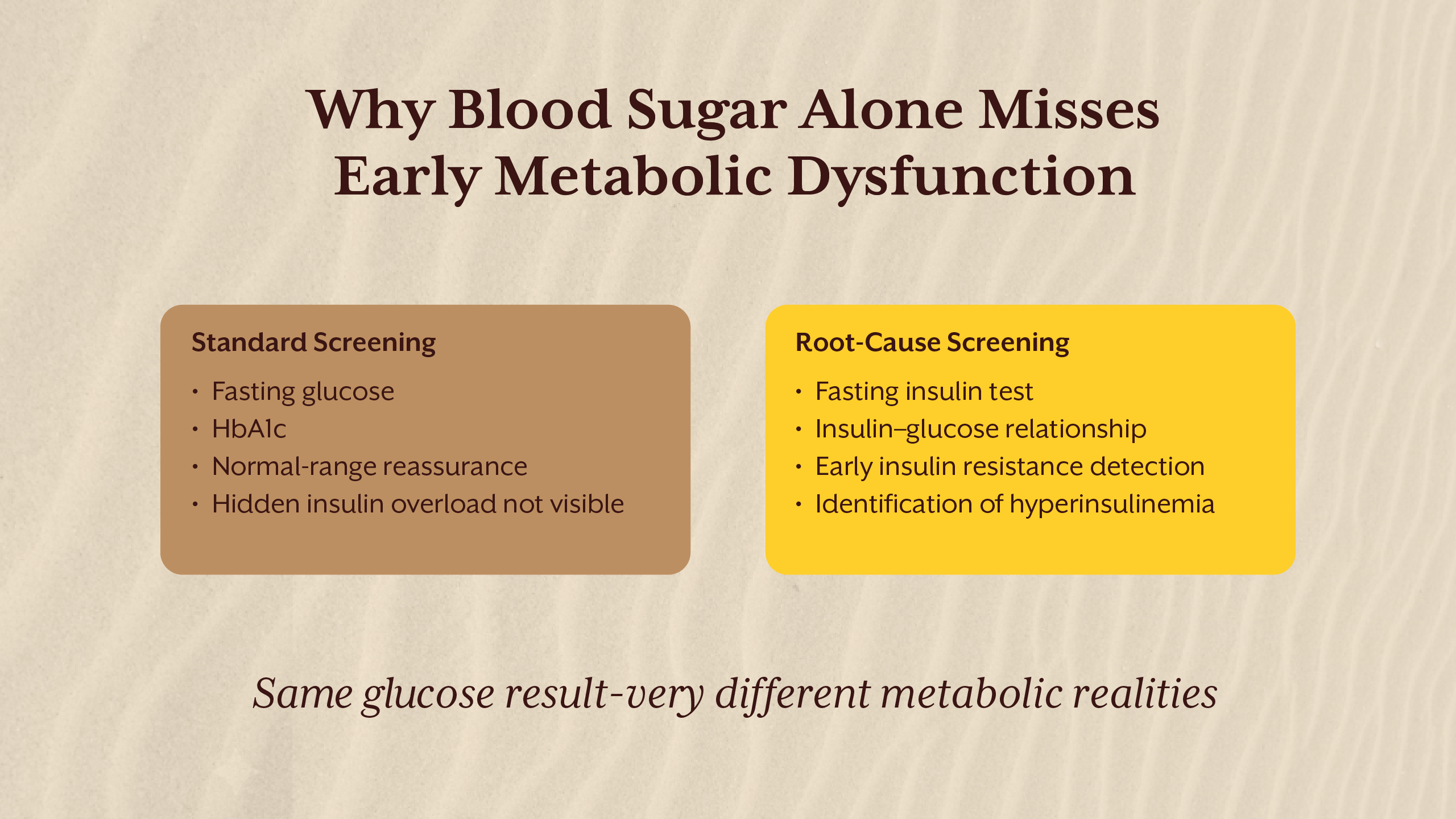

Importantly, hyperinsulinemia can exist even when fasting glucose and HbA1c remain within reference ranges. Blood sugar appears controlled only because insulin is working overtime. This distinction is critical, as glucose tests alone do not reveal the hormonal cost of maintaining that control.

Over time, chronically high insulin alters receptor sensitivity, cellular signaling, and metabolic flexibility, setting the stage for insulin resistance.

Why Elevated Insulin Is a Problem, Not a Solution

Insulin is often viewed as protective because it lowers blood glucose. However, chronically elevated insulin represents a state of metabolic stress. Cells exposed to high insulin for extended periods reduce receptor responsiveness as a protective mechanism, leading to insulin resistance.

High insulin levels also shift the body into a persistent storage mode. Fat breakdown is suppressed, lipogenesis increases, and metabolic flexibility declines. This makes weight loss increasingly difficult, even with calorie restriction.

Beyond metabolism, hyperinsulinemia influences inflammation, oxidative stress, and vascular function. Elevated insulin stimulates sympathetic nervous system activity, contributing to hypertension, and alters lipid metabolism, promoting atherogenic profiles.

Rather than preventing disease, prolonged hyperinsulinemia actively drives it.

The Missing Test: Why Insulin Levels Are Rarely Measured

Despite insulin’s central role in metabolic health, insulin levels are not routinely tested. Standard screening focuses on fasting glucose, post-prandial glucose, and HbA1c. These markers assess glycemia, not insulin dynamics.

The absence of insulin testing stems from historical disease models that defined diabetes by glucose thresholds rather than hormonal dysfunction. As long as glucose remains normal, insulin compensation goes unnoticed.

The insulin levels test, particularly the fasting insulin test, offers insight into how hard the pancreas is working to maintain glucose balance. Without this data, early metabolic dysfunction is often missed.

This gap explains why many individuals are diagnosed with insulin resistance or type 2 diabetes only after years of silent progression.

Hyperinsulinemia and Insulin Resistance: A Progressive Cycle

Hyperinsulinemia and insulin resistance reinforce each other in a self-perpetuating cycle. As cells become less responsive to insulin, the pancreas compensates by secreting more. This increased insulin exposure further reduces sensitivity, accelerating resistance.

This process does not occur uniformly. Liver cells, muscle tissue, and adipose tissue develop insulin resistance at different rates. The liver may continue producing glucose despite high insulin, while adipose tissue remains sensitive, promoting fat storage.

This tissue-specific resistance explains why individuals can experience fat gain, fatigue, and metabolic dysfunction long before glucose levels rise. Insulin resistance is therefore not a binary state but a spectrum of dysfunction across systems.

High Insulin Symptoms: Subtle but Persistent

High insulin symptoms are often nonspecific, which contributes to underrecognition. Individuals may experience chronic fatigue, increased hunger shortly after meals, difficulty losing weight, brain fog, and afternoon energy crashes.

Other insulin resistance symptoms include increased abdominal fat, sugar cravings, poor exercise recovery, and disrupted sleep. In women, hyperinsulinemia may worsen androgen excess and menstrual irregularities. In men, it may contribute to reduced metabolic drive and visceral fat accumulation.

Because these symptoms overlap with stress, aging, or lifestyle issues, they are rarely linked back to insulin dysregulation in clinical settings.

Insulin Resistance Causes: A Systems Perspective

Insulin resistance does not arise from a single dietary choice. It reflects cumulative metabolic strain from multiple inputs. Frequent eating without metabolic rest keeps insulin elevated throughout the day, preventing baseline recovery.

Chronic psychological stress increases cortisol, which raises glucose output and worsens insulin resistance. Sleep deprivation impairs insulin signaling and mitochondrial function. Circadian misalignment disrupts hormonal rhythms essential for glucose handling.

Nutrient deficiencies, particularly magnesium, chromium, and B vitamins, impair insulin signaling pathways. Gut-derived inflammation further interferes with receptor function.

Understanding insulin resistance causes requires a systems-level lens rather than isolated blame on sugar or calories.

Measuring What Matters: Fasting Insulin and Beyond

The fasting insulin test is one of the most valuable yet underutilized tools in metabolic assessment. It reflects baseline insulin demand and provides early insight into compensation.

Normal insulin levels vary across labs, but optimal fasting insulin is generally lower than what is considered “acceptable.” Elevated fasting insulin indicates that insulin resistance is already present, even if glucose remains normal.

Pairing fasting insulin with fasting glucose allows assessment of insulin sensitivity and metabolic efficiency. Tracking trends over time is often more informative than single measurements.

IThrive’s screening model prioritizes these early signals to identify dysfunction before irreversible damage occurs. This approach is discussed further in our Academy content on fasting insulin and early metabolic screening.

Insulin Resistance Treatment: Addressing the Root

Insulin resistance treatment is most effective when it reduces insulin demand rather than forcing glucose down. This requires restoring insulin sensitivity, not overriding physiology.

Dietary strategies focus on reducing glycemic load, improving meal timing, and allowing sufficient fasting periods. Strategic fasting, when individualized, lowers baseline insulin and allows receptor resensitization.

Lifestyle interventions such as sleep optimization, stress regulation, and circadian alignment directly improve insulin signaling. Nutrient repletion supports mitochondrial function and glucose oxidation.

This root-cause approach contrasts with glucose-centric management, which often leaves hyperinsulinemia unaddressed.

Why Hyperinsulinemia Matters Even Without Diabetes

Hyperinsulinemia is not a neutral state. Chronic high insulin accelerates fat accumulation, promotes inflammation, and increases cardiometabolic risk independent of glucose levels.

It is strongly associated with obesity, fatty liver disease, hypertension, dyslipidemia, and cognitive decline. In many cases, type 2 diabetes represents the late manifestation of years of insulin overload.

Identifying and addressing hyperinsulinemia early preserves metabolic flexibility and reduces long-term disease risk.

For those seeking clarity on whether insulin resistance or hyperinsulinemia may already be present, a root cause analysis can provide direction. You may choose to book a free consult to understand whether deeper metabolic evaluation is appropriate.

Key Takeaways

Hyperinsulinemia represents one of the earliest and most overlooked signals of metabolic dysfunction, often developing years before blood sugar levels become abnormal. Chronically high insulin levels reflect a state of compensation, not metabolic health, and quietly drive insulin resistance, fat accumulation, inflammation, and long-term cardiometabolic risk. Because routine screening rarely includes insulin testing, many individuals remain unaware of this condition until later stages of disease emerge. Measuring fasting insulin and addressing the underlying drivers of insulin resistance allows intervention at a stage where metabolic flexibility can still be restored, shifting care from late-stage management to true root-cause resolution.

Subscribe to our newsletter and receive a selection of cool articles every week

.png)

.webp)

.jpg)